T1.W(X) T1.W(Y) T2.R(X) T3.R(Y) T2.W(X) T3.W(Y)

Conflict Elision in Serializability

Classic database courses teach about conflict serializability. One is given a history of operations, and asked "is it serializable?"

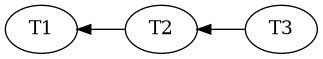

The taught algorithm for answering this question is to form the precedence graph, by constructing a graph annotating the existing conflicts:

-

Read-After-Write: If T2 reads a value written by T1, then T2 must commit after T1.

-

Write-After-Write: If T2 overwrites a value written by T1, then T2 must commit after T1.

-

Write-After-Read: If T2 overwrites a value read by T1, then T2 must commit after T1.

And then with our graph of "commit-after" relationships completed, we check for a cycle:

There is no cycle, and thus our history is serializable.

Instead, one can equally view this as a game of swapping the positions of adjacent operations. Our starting puzzle is a jumbled interleaving of transactions' operations. Our desired ending state is one in which each transaction’s operations are all adjacent. The ability to switch the positions of two operations are constrained by the same rules from above: if the two operations conflict, we may not exchange their positions.

Using our example above, we can make one swap:

T1.W(X) T1.W(Y) T2.R(X) T3.R(Y) T2.W(X) T3.W(Y)

X

T1.W(X) T1.W(Y) T2.R(X) T2.W(X) T3.R(Y) T3.W(Y)

and now all of T1’s, T2’s, and T3’s operations are grouped together, in that order, while respecting conflicting operations. Serializability is defined as "being equivalent to a serial schedule of transactions", and our swap has transformed the history into exactly that of a serial execution of T1, T2, then T3. Thus, the history is serializable.

This perspective on serializability testing as a game of swapping operations isn’t as useful as a procedural algorithm for testing serializability, but I propose that it is more useful for understanding how serializable databases behave. Databases classes teach serializability from the most conservative perspective, but in real world systems, every serializable database seems to break the exact rules of conflict serializability one is taught such systems must uphold:

-

Spanner permits concurrent writes to the same item via shared writer locks, which implies it doesn’t check write-write conflicts.

-

FoundationDB only checks write-after-read conflicts.

-

Cockroach doesn’t check write-after-read conflicts.

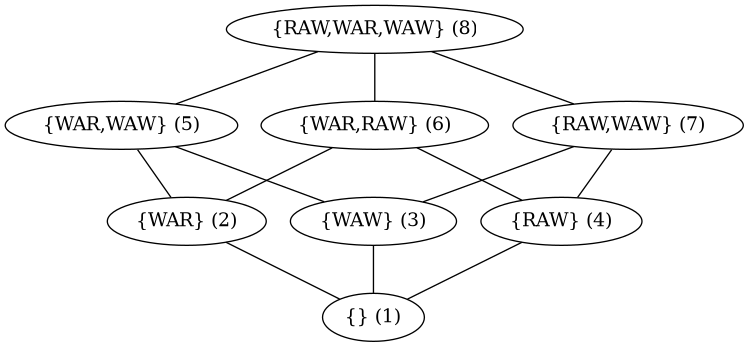

These databases each elide one or more forms of conflict checking, and yet these databases are still correct in describing themselves as serializable! To understand conflict elision, we approach the topic from the opposite direction: what does considering each type of conflict enable in terms of operation reordering? Then to tie it all together, we’ll cover example database architectures which permit eliding combinations of conflicts due to preventing the unserializable behavior by design.

Architecting for Conflcit Elision

For this post, our mental model of a database is that it records the (transaction, operation, item) tuple for each read and write it processes, in the order that they happen. When a transaction wishes to commit, the database filters the history of operations down to the ones from committed transactions or from the transaction in question, ensures reads didn’t return results from uncommitted writes, and then asks our serializability testing procedure "is this new history of operations serializable?". If so, it means the transaction is allowed to commit, if not, the transaction is aborted and all operations are removed from the history (and any transactions which read its uncommitted writes are also aborted).

The database is in control of when it allows an operation to execute, and thus at what point in the history it is inserted. It could be appended onto the end, it could be placed anywhere in the middle. By enforcing varying rules about when, where, and how operations are executed and placed into the history, the database is able to promise that it will prevent certain types of transaction conflicts from occurring at all, and so the serializability validation procedure may trivially assume they don’t exist. This post is about when we can not check certain types of these conflicts. Combining them gives us a lattice, and for each combination, we’ll consider a hypothetical system for which that combination of conflicts is the correct and minimal set of conflicts which need to be validated.

(1) Check Nothing / Elide Everything

To reiterate, serializability is defined as a history of operations which is equivalent to executing each transaction in some sequential order. If our system executes transactions one at a time, sequentially, there’s no need for any conflict checking to be able to say that this system is serializable.

This is not as ridiculous as it might sound. Calvin (and all of its variants), VoltDB, and TigerBeetle all adopt this model by ordering transactions first, and then executing them in that order.

In the context of our operation reordering game, the database promises that every time it adds a new transaction, it appends all of the transaction’s reads and writes in one contiguous grouping. No operation swapping will thus ever be needed to

(2) Check WAR / Elide WAW & WAR

T1.R(X) T2.W(X) Conflict: T2 must commit after T1 T1.R(X) T2.W(Y) No Conflict: Equivalent to T2.W(Y) T1.R(X)

Checking Write-After-Read conflicts means that we’re allowed to exchange two operations where the operation on the left is a read, and the operation on the right is a write. Thus, Write-After-Read conflicts are about moving reads forward in version-time, and moving writes backwards in version time.

This is one of the most commonly encountered sets of conflict elisions. If all reads are performed before all writes, then we’ll only ever need to swap writes forward or writes backwards for the two to meet. The decision of moving reads to the commit timestamp or moving writes to the read timestamp is up to the database. Moving reads for

(3) Check WAW / Elide WAR & RAW

By considering write-write conflicts, we are allowed to re-order writes in the operation history, because the system records when it’s not safe to (via recording the write-write conflict). It’s always safe to swap the order of two writes to different keys, but that swapping the order of two writes to the same key might result in unserializable behavior.

I like to think of write-write conflicts as the defenders of transaction atomicity. Given two transactions $T_1$ and $T_2$, which each perform a write to $X$ and a write to $Y$, we can only break atomicity by allowing writes from the two transactions to be interleaved:

Not Serializable: T1.W(X) T2.W(X) T2.W(Y) T1.W(Y)

Ending state: T2's X. T1's Y.

Serializable: T1.W(X) T1.W(Y) T2.W(X) T2.W(Y)

Ending state: T2's X. T2's Y.

And so write-write conflicts are preventing the database from reaching a state where a subsequent read of all values in the database would not be serializable.

(4) Check RAW / Elide WAW & WAR

T1.W(X) T2.R(X) Conflict: T2 must commit after T1.

Checking RAW conflicts means that we’re permitted to swap a write and a read, where the read occurs after the write, and the read and the write are on different items.

This importantly allows reads to be pulled backwards in the ordering, or writes to be pulled forwards. Generally, this alone isn’t a particularly useful way to be able to swap operations. In most transactions, the reads are performed before the writes, and thus one would always wish to move reads forward or writes backward.

Allow us to instead consider a database based around financial transactions[1]. The database supports one form of transaction: apply an increment to one account, a decrement to another, and ensure that the decremented account doesn’t drop below zero. One could implement such a system by first logging the increment and decrement operations, and then issuing a read through the levels of an LSM, collecting other increment and decrement operations, until it reaches a final value and sums all discovered operations. If the read encountered any (other) uncommitted increments or decrements, then establish a transaction dependency on the uncommitted transaction. If the read returns a greater-than-zero value, swap the read operation with other reads and writes in the history until it reaches the write

[1]: I swear I’m not referencing TigerBeetle.

Write-Write Conflict Elision

Accordingly, write-write conflicts are the most frequently elided form of conflicts.

Thomas write rule.

In multi-version concurrency control, all writes for a transaction appear in the same version, and thus are always appended onto the history of operations in one large group. It’s impossible for two individual operations from two transactions to interleave. If one never tries to re-order entire transaction groups worth of writes, then there’s no need to ever pay attention to write-write conflicts.

Formally, such a property is called "write snapshots", and was introduced in "A critique of snapshot isolation".

As a last note before we move on, there’s a consistent theme in serializability, and concurrency control in general, that one is allowed to break any rule at any time as long one can ensure that a user will never be able to prove that a rule was broken.

An often taught, but seldom used way to break the rules of write-write conflicts are allowing commutative operations to be freely reordered. For example, any ordering of increments and decrements result in the same final value, and so enforcing an order on them isn’t necessary if one can never witness the intermediate values. This is what increment locks permit, or more generally, escrow transactions.

In the context of our operation swapping game,

You do need to check write-after-write conflicts if:

-

Your writes are performed across a range of versions OR it is a single-version database.

-

You are implementing SQL isolation levels, which mandate write-after-write conflict checking as part of the "lost update" anomaly restriction.

You do not need to check write-after-write conflicts if:

-

Writes all appear atomically in the same version. (e.g. with MVCC)

-

The "writes" are commutative operations (e.g. increment), or you implement escrow transactions.

Read-After-Write Conflicts

Read-after-write conflicts are all about writes moving to the right or reads moving to the left in our version diagram.

Of the three, these are the most commonly elided conflicts, but they’re still possible. SQL constraint checking might need to do reads, writes, reads. The latter reads could move backwards. The former reads could move forwards.

You do need to check read-after-write conflicts if:

-

Reads are performed across a range of versions OR it is a single-version database.

-

At commit, reads can be serialized at an earlier version than when they were performed.

-

At commit, writes can be serialized at a later version than when they were performed.

Write-After-Read Conflics

It’s very common for reads to be serialized later than when they were performed. These

You do need to check write-after-read conflicts if:

-

Your reads are performed across a range of versions OR it is a single-version database.

-

At commit, reads can be serialized at a later version than when they were performed.

-

At commit, writes can be serialized at an earlier version than when they were performed.

I Can’t Believe It’s Not Serializability

How do you elide checking conflicts?

Key optimizations:

Read Snapshots Write Snapshots

Not all serializability is equal

serializability classes

history vs scheduler

2PL restrictive SSI less restrictive serializable safety net

See discussion of this page on Reddit, Hacker News, and Lobsters.